Balthasar Burkhard/© J. Paul Getty Trust/Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Harald Szeemann (seated) on the last night of ‘Documenta 5: Questioning Reality—Image Worlds Today,’ Kassel, Germany, 1972

A restaurant near my apartment sells “curated salads”; a home goods store sells “carefully curated sheets”; a babysitting agency offers “curated care”; my inbox bulges with curated newsletters, curated dating apps, curated wine programs. Kanye West, the Trumpist rapper, calls himself a curator, as do Chris Anderson, who runs TED Talks, and Josh Ostrovsky, who under the name the Fat Jew spews plagiarized jokes and alcohol advertising to millions of followers on social media. It’s been well over a decade now since the figure of the curator—a once auxiliary player in the world of art—became vulgarized and generalized in consumer society, and still its demented currency endures; you can eat burgers at the Curator restaurant at Heathrow Airport. Actual curators, by which I mean the people who care for objects in museums and organize exhibitions and biennials, have had to start looking for new titles. (Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, this year’s winner of a major prize for curators, prefers “draftsperson.” She says, “You curate pork to make prosciutto.”)

The curator, especially the curator of contemporary art, is a young figure in art history; we critics have thousands of years on them. Aristocrats, physicians, and clergymen proudly oversaw the connoisseurship and display of their own Wunderkammern in the early modern period, while at the Louvre, the first of the national museums established in the late eighteenth century, the décorateurs who hung paintings and installed sculptures were artists themselves. Audiences discovered new painting and sculpture at artist-juried exhibitions such as the Salon in Paris, and later at commercial art galleries; braver souls might first see the modernist avant-gardes in exhibitions artists organized on their own.

Only in the middle of the twentieth century did the curated exhibition take over from the salon, the dealership, and the independent show as the principal launch pad of contemporary art. In fits and starts, the professional curator arrogated responsibilities once held by the artist, the collector, the historian, or indeed the critic, becoming the figure who assigned meaning and importance to new art: someone the art historian Bruce Altshuler has called “the curator as creator.” Soon after, the curator stepped beyond the single museum or institution to become a roving organizer and analyst of contemporary art.

In the United States, the paragon of this authorial form of curating contemporary art was Walter Hopps, a Californian who in the 1960s offered the first museum retrospectives of Marcel Duchamp and other living artists. (He later became the first director of the Menil Collection in Houston.) In Europe, it was Harald Szeemann, a shaggy Swiss savant whose early career at a small, noncollecting institution prefigured nearly four decades of organizing and circulating large-scale exhibitions. From his unruly headquarters in the mountains of Ticino, where his papers and books filled an entire warehouse he called the Fabbrica Rosa, Szeemann—who died in 2005 aged seventy-one—planned exhibitions of contemporary art “from vision to nail.” Some were staged in the world’s largest museums, others on view in private apartments or hilltop redoubts. Self-supporting, self-assured, with a Rabelaisian appetite for both art and life, Szeemann became the prototype for the frequent-flying contemporary art curator who emerged at the turn of the twenty-first century, bleary-eyed, with his crumpled Prada suit and dinged Rimowa suitcase, in the arrival terminals of Venice and São Paulo and Hong Kong.

In 2011 the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles took ownership of the Fabbrica Rosa—the largest single archive it has ever acquired. Szeemann’s catalogs, letters, photographs, hand-sketched exhibition layouts, and scribbled artist rosters were on view last year in a comprehensive exhibition at the Getty (which then toured to three European museums), and they’re assembled, too, in the hefty volume Museum of Obsessions, packed with scholarly essays and interviews on Szeemann’s expansive career. The Getty has also published a volume of Szeemann’s translated writings, while another fraction of the archive was deployed in the recreation of one of Szeemann’s weirdest and most important shows: “Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us,” an obsessive reconstitution of the life and collection of his grandfather, who was a hairdresser. First seen in Los Angeles last year, “Grandfather” finished its tour this summer at Swiss Institute in New York’s East Village, and it contained no art as such. Instead, one discovered more than a thousand historical objects and documents Szeemann had preserved and kept in the Fabbrica Rosa archive, all presented within freestanding temporary walls that replicated the dimensions of the show’s first venue: his own Bern apartment.

The very act of restaging a decades-old exhibition, from the placement of walls to the design of the displays, suggests how thoroughly the object of inquiry in contemporary art has passed from individual artworks to full-scale shows. (And this is not Szeemann’s first to be resuscitated; in 2013 the Fondazione Prada in Venice restaged “When Attitudes Become Form,” his breakthrough 1969 exhibition of postminimal sculpture and conceptual art.) But the richly illustrated Museum of Obsessions does not aim to replicate his shows on paper, and does not even include a list of the more than 150 exhibitions he curated.*

“The fact that Harald Szeemann was a curator,” writes Glenn Phillips in the introduction to Museum of Obsessions, “is not the thing that makes him interesting.” That sounds a bit like a rearguard action to those of us who’ve eaten one too many “curated” sandwiches and frowned at hotels’ “curated” pillow menus, as if the editors want to insulate him after the fact from the generalization and dilution of the curatorial mode. Yet perhaps Szeemann, who always called himself an Austellungsmacher (a maker of exhibitions), would have liked the abnegation. For this king of curators was also his own public relations officer, his own technical chief, his own accountant—and, as countless Getty employees and interns have since learned, his own diligent archivist.

Harald Szeemann was born in Bern in 1933, into a family of hairdressers. In his teenage years he started a cabaret, but he left the theater for art history, eventually completing a Ph.D. on French modernism at the University of Bern and, later, the Sorbonne. The natural decision for a newcomer of his ambition, in the hundred years before 1961, would have been to stay in Paris. But the young Szeemann noticed that the most interesting European art—and the most interesting exhibitions, which was beginning to mean the same thing—had shifted out of the French capital and toward internationally minded museums to the north, in particular the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam under Willem Sandberg (which Szeemann visited every month) and Moderna Museet in Stockholm, led by Pontus Hultén.

So Szeemann stayed in Switzerland. He had already curated his first exhibition, on the theme of poets and painters, for the Museum St. Gallen, where “the intensity of the work made me realize this [making exhibitions] was my medium. It gives you the same rhythm as in theater, only you don’t have to be on stage constantly.” In 1961, aged twenty-eight, he was named director of the Kunsthalle Bern, an exhibition hall governed by a local artists’ union. These days the Kunsthallen of German-speaking Europe host big-ticket shows and publish authoritative catalogs, but in the early 1960s the Kunsthalle Bern had a staff of three, a piddling budget of 60,000 Swiss francs (“My whiskey consumption took care of my salary in no time”), and just a few hours’ turnaround time between shows. The straitened circumstances enjoined Szeemann to collaborate with institutions like the Stedelijk, whose larger budget he relied on to ship over the work of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and other American artists. He also improvised thematic exhibitions like “12 Environments” (1968), for which artists came to Bern to fill, slather, and overwhelm the galleries, while Christo draped the Kunsthalle’s functionalist building with a plastic sheet. Christo, interviewed for Museum of Obsessions, relates that the show so irritated Bernese art audiences that someone wrapped Szeemann’s Volkswagen Beetle in retaliation.

The local press regularly flayed him, but people outside Switzerland were talking about sleepy Bern, and on the strength of “12 Environments” the tobacco company Philip Morris made Szeemann a very strange offer: a no-strings-attached budget of $150,000 (more than $1 million in 2019 dollars) to organize any show he wanted. Even in 1968 such corporate hand-washing could raise hackles (Hultén, at Moderna Museet, had faced protests for accepting tobacco company sponsorship), but the chain-smoking Szeemann pocketed it gleefully. He used the cash to travel to America—in Museum of Obsessions you can see his densely annotated address book, with phone numbers for Bruce Nauman and Robert Ryman in New York, Ed Ruscha and Mary Corse in Los Angeles. Back in Bern in 1969, he blew the rest of the tobacco money on an exhibition that would leave the most fundamental principles of aesthetic appreciation in tatters.

“When Attitudes Become Form”—or, to give its unwieldy full title, “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form; Works—Concepts—Processes—Situations—Information”—brought to Bern sixty-nine radical young artists, many of whom have since become demigods, whose work could exist either in real, material form or else in imagined, conceptual, rumored, or otherwise immaterial modes. Richard Serra showed up to splash molten lead into the corner of the museum. Joseph Beuys smeared another corner with fat. Lawrence Weiner excised one square meter of a gallery wall. Michael Heizer took a boulder and smashed up the sidewalk. Many of the artists made, or conceived yet did not make, art far from the Kunsthalle: the British artist Richard Long did nothing but hike for four days in the Berner Oberland. Walter De Maria stayed in New York and made very occasional calls to a telephone in the gallery.

“When Attitudes Become Form” short-circuited what Szeemann called “the studio-museum-gallery triangle”: the pathway of modern art from the artist’s studio, via the commercial gallery, to the public or private collection. In its place it proposed a more pervasive, even numinous conception of art that has endured ever since. It insisted that “art” is a whole bundle of activities, stretching past autonomous images and objects, that encompasses being an artist, speaking like an artist, and acting like an artist within a specific setting. It proposed that texts, recordings, and other forms of documentation were integral components of artistic creation, and that the eyes were insufficient to perceive a work of art in its totality. And it positioned the curator as an active agent in artistic creation, perhaps even an author or an Über-artist. (The artist Daniel Buren would later complain that Szeemann was exhibiting his work as mere “brushstrokes in his [i.e., Szeemann’s] painting”; the curator generously published the insult in the exhibition’s catalog.)

Even if some of these propositions had their roots in Dada and other modernist tendencies, they were still not common currency in the 1960s, and “When Attitudes Become Form” set off a national scandal. “Is Art Finally Dead?” read one magazine headline. Artists dumped a pile of manure outside the front door. Szeemann was forced to resign as artistic director of the Kunsthalle, and he would never again hold a job. Later in 1969 he established the Agentur für geistige Gastarbeit (Agency for Spiritual Guest Labor): a one-man operation for the production of exhibitions, tarted up with pseudocorporate letterhead and official-looking stamps and seals. With the Agentur, Szeemann essentially invented the position of the freelance curator, organizing and circulating exhibitions at museums in Switzerland, across Europe, and as far afield as Sydney.

“When Attitudes Become Form” made enough of an impact that Arnold Bode, the founder of Documenta, invited Szeemann to organize its fifth edition. Documenta is a giant exhibition held every four or five years in Kassel, Germany (running from June to September, it is known as the “museum of 100 days”), founded in 1955 to redeem large-scale German art exhibitions after the Degenerate Art Show of the Nazi era. But it had badly misstepped in 1968 with a conservative, American-heavy edition that incited protests and boycotts. Bode heard the demands for a new direction at Documenta and found, in Szeemann, a figure who could inscribe the era’s countercultural protests and avant-garde impostures inside his institution, when others wanted to tear it down entirely.

If Documenta is now the world’s most important exhibition of contemporary art, that is largely the legacy of Szeemann’s edition of 1972, for which he reassembled most of the postminimal and conceptual artists of “When Attitudes Become Form,” but also included photorealism, hyperrealistic sculpture, political propaganda, and the art of the mentally ill, all of which typified what he called “individuelle Mythologien” (individual mythologies). Large-scale international exhibitions of new art were already well established (the Venice Biennale by then was more than seventy-five years old), but Szeemann’s Documenta established the megashow as we imagine it today: a thesis-driven presentation with a unified mode of display; bold, often temporary public interventions; and theoretical discourses in the form of catalogs, debates, performances, and interviews. “The notion of innovation was no longer sufficiently attractive,” Szeemann later wrote, “and an accumulation of painters was replaced by the exhibition as Gesamtkunstwerk.”

But a Gesamtkunstwerk is not a democratic endeavor. Farewell to the Salon jury or the independent artists’ group; in their place was the curator as gatekeeper, designer, chief theoretician, and impresario. The critic Barbara Rose, in New York magazine, called the show “a kind of Disneyland as designed by Hieronymus Bosch,” and took an ironic pleasure in how thoroughly Szeemann had institutionalized the avant-garde: “Every strategy and ploy of the contemporary artist to remain outside of society and critical of its institutions is proved useless.” Serra, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, and other American artists decried this new curatorial dominance in an open letter to the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, insisting that artists alone should govern their work’s presentation in the gallery and interpretation in the catalog.

Rose, going further, averred that Documenta 5 really had only one artist: the “brilliant” Szeemann himself, “the greatest conceptual artist in the world.” But I’m not sure Szeemann was an artist manqué so much as a compulsive accumulator of artistic information—and he might have had loftier career goals than any artist. Looking back on his appointment to direct the Kunsthalle Bern, he spoke of himself as “the world’s youngest museum director, the first Catholic director in Protestant Bern. There were some similarities to John F. Kennedy.” He invited both Mao and Nixon to Documenta; neither replied. From Kassel he fired off a letter to the United Nations, inquiring as to whether his artistic diplomacy might be channeled elsewhere:

Sirs, I heard this evening at the local radio station that Mr. U Thant will give up his job at the end of this year. I like him. If he is willing to stay another year I would be glad to present myself as a candidate to this very [taxing] job of general secretary.

Only seven thousand people ever saw “When Attitudes Become Form” in Bern—its renown, then and now, depended on photographic documentation and coverage in art magazines. But Documenta 5 introduced some 220,000 visitors to Szeemann’s expanded field of art and visual culture. Most of the press was brutal, and even Jürgen Habermas, whom Szeemann expected to appreciate Documenta 5’s emphasis on communication and interaction, said Chuck Close and the other photorealists were all he could make sense of. The show also went over budget; the city of Kassel sued him for liability. Morris and his fellow American detractors imagined Szeemann to be an art-world dictator, but he was, by 1973, essentially broke.

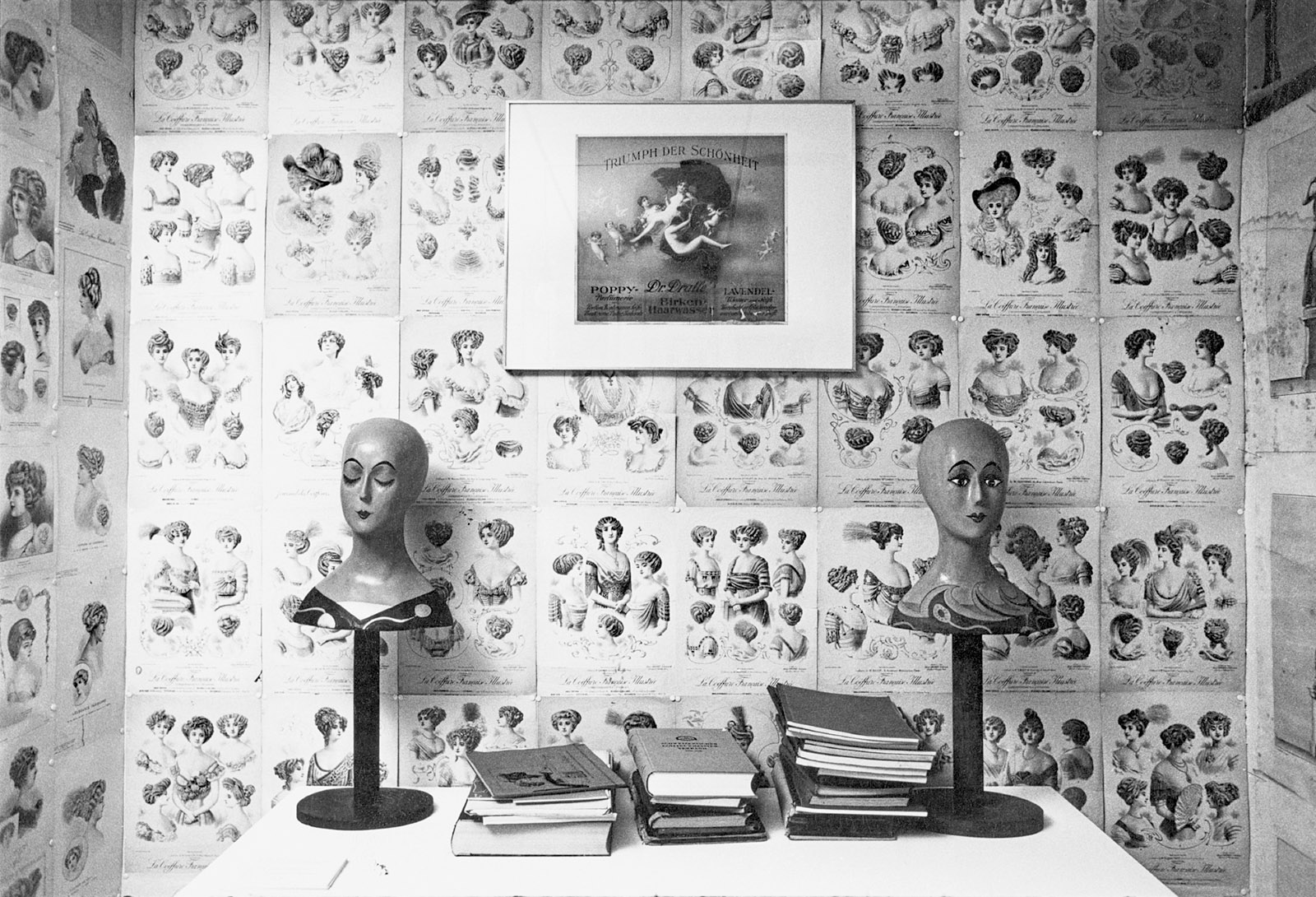

Back in Bern, he withdrew from the large-format exhibition to create the strangest show of his career. “Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us,” staged in his apartment in the spring of 1974, was a tribute to his late grandfather Étienne Szeemann, a high-end hairstylist who also invented a permanent-wave machine. “Grandfather” included more than 1,200 hairdressing tools, cosmetics, dolls, teacups, and documents, carefully organized by chronology, geographical origin, color, and theme. These objects did more than relate Étienne Szeemann’s migration from Hungary, professional success, and family life. They also, in Harald Szeemann’s presentation, outlined a half-century’s cultural history, with hairdressing as a funhouse reflection of the modernist avant-garde. Wig stands in the form of bald, big-eyed maidens became Surrealist totems. A framed Helvetian white cross on a red field, which the elder Szeemann made after he took Swiss citizenship in 1919, is crafted from dyed human hair. His worrying perm machine, topped by a dozen tangled metal cylinders dangling from wires, looks rather like an electric chair.

Rich, dense, and tinged with melancholy, “Grandfather” owed a profound debt to another roving assemblage of mundane objects: the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers’s Musée d’art moderne, département des aigles, which mapped centuries of national and European history through an aggregation of hundreds of postcards and tchotchkes of eagles. (First shown in Broodthaers’s Brussels apartment in 1968, the mock museum traveled to Szeemann’s Documenta 5.) Phillips, in Museum of Obsessions, glosses “Grandfather” as “a symbol of curating in its purest form—exhibition making as a creative act, curating for curating’s sake.” Its full-scale restaging, with nearly all the original objects, is an achievement perhaps only the Getty could pull off, and demonstrates that archival curating, far from a programmatic exercise, is capable of eliciting the most intense emotions.

Balthasar Burkhard/© J. Paul Getty Trust/Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Installation view of Harald Szeemann’s ‘Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us,’ Bern, 1974

If “Grandfather” romanticized and miniaturized the individual mythologies Szeemann appreciated in the artists of Documenta 5, it also cleared the path for several of his later exhibitions, particularly the touring show “Bachelor Machines” (1975–1977). Drawing on Duchamp’s intertwining of erotics and mechanics, “Bachelor Machines” narrated an onanistic history of modernism in which engines and contraptions get confused for flesh and blood. Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel, a bicycle wheel fastened to a stool, stood next to the Swiss sculptor Robert Müller’s La Veuve du Coureur, a stationary bike whose pedals powered a phallus that rose and fell through the saddle. Szeemann also commissioned several models of bachelor machines from literature, most fearsomely a full-scale rendition of the torture device in Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony,” which tattoos a condemned prisoner with the law he has broken. (Several objects from “Grandfather” were included, though not the perm chair; it would have fit right in.)

As so often with Szeemann, “Bachelor Machines” grafted the art of his contemporaries onto an earlier, messier modernism of the 1880s to the 1920s, typified by Duchamp, Kafka, Raymond Roussel, and the earlier pataphysics of Alfred Jarry, the author of Ubu Roi. (The years around World War II did not interest Szeemann much, and he almost never exhibited Abstract Expressionism.) His other major show of the 1970s, “Monte Verità,” warmer and freer than the closed circuit of “Bachelor Machines,” studied a collection of spiritualists, utopians, anarchists, and vegetarians who all came to the titular mountain in the years around 1900. You can still see this permanent exhibition in a house in Ascona, Switzerland—and “Monte Verità” may, more than any other show, typify Szeemann’s advocacy for a blending of art and life, with one foot planted in the mountains and the other traipsing around Europe.

Nam June Paik, speaking to a Swiss television station in 1992, celebrated Szeemann as “one of few guy [sic] who can combine the impetus and the anger and the rebellion of our underground artists…with institutions and money people and bankers…. Art world’s problem is that all radical people must live on the most dirty rascals’ money.” Szeemann’s later career, often focusing on national art scenes (Austria, Belgium, Spain, the Balkans) and culminating in two editions of the Venice Biennale in 1999 and 2001, tried to reconcile those two camps, and the results were mixed. These late shows had larger budgets, drew larger audiences, but had little of the fissiparous invention and theoretical heft of “Grandfather,” “Bachelor Machines,” and the other achievements of the 1970s.

The one place he could hold onto the spirit of that era was up near Monte Verità, in the ever-growing archive of the Fabbrica Rosa, which held in tension the curator’s Apollonian impulse to organize and Dionysian drive to freedom. Christov-Bakargiev, who curated Documenta in 2012, writes in Museum of Obsessions that this extended even to Szeemann’s drinking habits: “For forty years he drank a simple midrange Ticino merlot…and used the cardboard boxes that the wine bottles had been packed in as containers for his archive…so that ‘the more I drink, the more I organize.’”

Artists called Szeemann “King Harry,” but is the curator still the boss? By the late 1990s, the institutionalization of the avant-garde that began with “When Attitudes Become Form” had begotten a global network of biennials, fairs, schools, and publications. My generation of artists and writers (I’m thirty-six) treated curators like Okwui Enwezor and Vasıf Kortun with the intellectual deference our predecessors reserved for critics like Clement Greenberg and Rosalind Krauss. Art historians began to study the “history of exhibitions,” and “curatorial studies” programs proliferated outside the traditional academy and even within it, at institutions like my alma mater, the Courtauld Institute of Art.

Now these curatorial studies graduates fill the seats of every EasyJet flight from Brussels to Berlin, banging out catalog entries for one of three-hundred-odd biennials worldwide. Almost none, though, have the authority (or the budgets) that Szeemann and his immediate heirs commanded, for better and worse. When Szeemann quit the Kunsthalle Bern to work as a freelance curator, he imagined his withdrawal as part of “the spirit of ’68.” The art historian Beatrice von Bismarck proposes in Museum of Obsessions that his career in fact presages today’s post-Fordist, “immaterial” conception of work—in which the manufacture of objects has been superseded by managing, organizing, displaying, and advising, and even the most senior figures work on a project-to-project basis.

Today’s young curators have not only come of age when artists themselves can regulate their own attention through digital networks, and when their art often involves the remixing and redeployment of preexisting images. They also must fight for attention when all of us are marketing a “curated” self to our friends, lovers, coworkers, and sponsors, and where each day human classifications and judgments increasingly give way to algorithmic “curation.” (Every Instagram feed is a curated show of one’s own.) Add to this a deep skepticism of the all-encompassing visions of “When Attitudes Become Form” and “Bachelor Machines”—for a certain sort of younger curator, every interpretation from above is an act of violence—and you can understand why so many sound more like social workers and educators, committed to “listening” and “learning,” than like master builders.

When I heard last February that Documenta 15 (to open in 2022, the fiftieth anniversary of Szeemann’s show) would be “drafted” by ten Indonesian artists planning to partner with Kassel’s local hospitals and youth soccer teams, it felt as if the curtain had come down on the old model of the curator as creator. We in the art world spent years laughing at the curated pizzas and curated nail salons, but the joke was on us: the practice of curating, in the Szeemannian sense of organizing ideas and images into meanings and narrative, really has been universalized and cheapened. This may not be a bad thing, and art today may benefit from a quieter, more modest, more collaborative approach to organizing exhibitions. But I suspect the standing of the curator is going the way of that of the critic, and no one ever built a monument to us.